It’s spring, finally. The snow is rapidly loosening it’s grip on the land. Pocket gophers and voles are still hunkered down beneath the small white patches that remain, and this experienced red fox is taking advantage of the cover that provides for hunting. Stay tuned to see whether she was successful...

Sunrise on the Firehole River

Sunrise on the Firehole River in Yellowstone. Yellowstone has no shortage of breathtaking rivers, but the Firehole is certainly chief among. Here, the water pools up before a waterfall plunges into a canyon.

A small tree growing up under a big shadow

Bull Bison in Grand Teton

This may be my favorite thing to see in the winter...a big bull bison covered in frost. The winter coat of a bison is so well insulating that there isn’t enough heat escaping their body to melt the frost. I’ve been able to photograph this bull several times over the last couple years. His exceptionally red coat, and the red patch on his face, make him easily recognizable.

Solitude - Winter in Yellowstone

Hayden Valley has always been my favorite region of Yellowstone, but photographing it all alone in the quiet of winter is an unforgettable and altogether different experience. We photographed this tree on one my recent photo tours.

Tatanka

Winter Wildlife Feature I - Bison

Featured first on this series of posts highlighting wildlife and their unique strategies for enduring Yellowstone winter is the bison. Two key assets equip bison to survive in this unforgiving climate.

The distinct shoulder hump on their back, which is actually a protruding muscle, allows them to function as a 1 ton, living snow plow. Unlike other ungulates, such as moose and elk, which scrape with their front feet to access food under the snow, bison use this muscle to rock their massive heads back and forth exposing grass and sedge buried under several feet of snow. Some bison will opt out on this “snow-plow” technique, preferring to graze alongside thermal features where the warm steam from geysers or hot springs melts the snow on the surrounding grass.

When violent winter storms hit, prompting other wildlife to seek shelter from the chilling wind and blinding snow, bison just plop down where they are and wait it out. Their winter coats are so thick and well insulated that the falling snow doesn’t even melt on their back. In a heavy snow, you can watch the largest land animal North America vanish before your eyes in a matter of moments.

Winter in Yellowstone - Intro

Winter in the Greater Yellowstone marries serene beauty and harsh realities in a way only an arctic like cold can. On some days you may be excused for mistakenly thinking you were located in the polar zone. Last January on my photography worksop we spent a day in the field with low temps reaching -40° F (40° C). Severe cold, blustering winds, and limited food resources present supreme challenges for wildlife to overcome. Nothing has kindled a deeper sense of respect for the fortitude and adaptability the inhabitants of this ecosystem posses than my time photographing them in the winter. The next series of posts over the coming days will highlight individual animals and their unique strategies for surviving, and even thriving in the gauntlet of winter.

The Ever-Watchful Eye...or Nose

If you are fortunate enough to see and photograph a mother grizzly bear like this one in Yellowstone, one of the first things you will notice is her careful attentiveness to her surroundings. Not only will she keep a watchful eye on her immediate environment, but she will also frequently pause to intentionally engage her most powerful sense, her nose. Her sense of smell is estimated to be 1,000x stronger than a humans. To help put that into perspective, a dog, whose sense of smell we use to detect bombs, is estimated to possess a sense of smell that is 70x stronger than a human. Imagine what we could do with a TSA grizzly. With this superpower, a mother grizzly is able to detect potential threats to her cubs from a considerable distance. When she detects danger in the air, her demeanor immediately alters. Standing up tall, she will sniff the air excessively while huffing at her cubs to alert them to the impending threat. Many times I have witnessed this behavior, and within 3o minutes a large male grizzly, which will kill bear cubs, arrives on the scene. Of course by the time I realize what posed the danger, the mother and cubs are long gone.

Yellowstone Harlequins - At Home Among Turbulent Waters

Harlequin ducks call home, what most would consider total chaos. These birds thrive in turbulent waters. Every spring Harlequins leave the rough surf of the Pacific Northwest, and migrate to inland to breed among various rapids and whitewater. The Lehardy Rapids of the Yellowstone River in Yellowstone National Park are considered the southernmost breeding location for these resilient ducks.

Sunset on Yellowstone Lake

Sunsets over the largest high elevation lake in North America never disappoint. Yellowstone Lake, claiming over 140 miles of shoreline, holds ice on its surface over half of the year. It would be natural to assume that all the water is freezing cold, and it would be if it were not for the volcanic forces responsible for shaping this landscape, which are still very active today. While surface is covered in an ice layer as thick as two feet, the water beneath reaches temperatures up to 252° F (122° C)!

Spring Grizzly

Hibernation is one of the most remarkable adaptations in nature. Imagine the effects on your body if you were confined to a bed for 5 months, and then imagine you did it without food. That's what this bear just did. Grizzlies are able to rely entirely on fat reserves during this time, and don't deplete any of their muscle mass.

Yellowstone Volcano

Hydrothermal features located throughout Yellowstone provide a visual reminder that the powerful volcanic forces which shaped this unique land are still very active today. Snow melt and rain water permeate below the earth's surface, where it is superheated by an immense magma reservoir, which at places is located only a couple miles beneath the earth’s crust. The water, reaching temperatures above 400ºF, then makes the journey back to the surface, resulting in geysers, hot springs, and thermal runoff.

American Legend

From the Native Americans and early frontier explorers to current day outdoor enthusiasts, perhaps no stories are told with more enthusiasm and pride than those of encounters with the grizzly. This is the emblematic face of the American wilderness. I am so thankful to live in one of the few places this creature still calls home.

"There is much about the grizzly and his characteristics which highly recommends him to our historic lore. He is American to the backbone and as noble, roughhewn, and fearsome as the emblematic lion of England, the winged bull of Assyria, dragon of China, sphinx of Egypt, or any other fabulous animalistic demigods of history...The bravest, toughest and most distinguished [frontier adventurers] have spoken with the greatest pride about their encounters with the grizzly-Lewis and Clark, Zebulon Pike, Kit Carson, Stonewall Jackson, General Custer, Theodore Roosevelt, and many more. Not one has held him lightly." - excerpt from The Beast that Walks Like a Man

Angry Squirrels

Throughout the year my time is mostly consumed with various photography projects and specific image goals. In these instances I know what subject I am photographing, and even the exact shot I am going for, such as the elk crossing the stream in the fog, or a Great Grey Owl flying in the snow. These images require excessive time scouting in the field to get one shot. I call this style “proactive” photography. In this proactive mindset I envision a scene I want beforehand and then go after it. I may not have control over all the elements, but I use research and knowledge to reduce as many variables as possible, and so increase the chances of making a truly remarkable image. However, this thoughtful approach to photography requires a lot of time, and some days I find myself playing catch up in the office and may only have a couple hours at the end of the day to get out in the field. Plus, there are times I just like to get outside with my camera and see what I can find. There is something about going out to photograph the unknown with an open and creative mindset that is relaxing.

On these days, while I may not have a specific subject in mind to photograph, I do have a plan; I listen to the squirrels.

Red Squirrels spend the summer and fall months harvesting pine cones and storing them in a cache known as a “Midden”. The Squirrels, being highly territorial and intolerant of any other creature in the vicinity of their middens, and also very small, resort to the best defense they know, an incessantly loud and obnoxious chatter. I realized the relevance of this knowledge for photography last year when I was looking for Great Grey Owls. I had just about thrown in the towel when I heard a squirrel alarm call which led me directly to the owl. Then it dawned on me…squirrels will bark at anything. If I simply wandered the woods following the sound of squirrel chatter I would likely have a higher success rate in locating owls, but I wonder what else I would find?

The next day I entered the woods armed with my new tactic. Eyes closed, I stood in silence and listened. No more than a minute had passed and I heard it. The angry squirrel. I followed the sound to the scene where I discovered two squirrels fighting. Entertaining to watch, but not what I was hoping for. A few moments later the sound of another defensive squirrel came ringing through the woods from the east. I arrived at the scene and found the squirrel barking up a storm from its lofty perch in a lodgepole pine, but was clueless as to what set it off. As I spun in another circle scanning the area, the culprit emerged from behind a log. A pine marten! The initially timid weasel was now overcome with curiosity and began to approach me. I stood still until it was comfortable with my presence and resumed the evening hunt.

After an hour of tripping over logs trying to keep up with the marten, I decided to put the last hour of light towards finding another angry squirrel. I slowly walked along a stream bank about 300 yards, and heard another alarm call to the south. The call led me to the edge of a small meadow where I found a Great Grey Owl intently focused on a light rustle in the grass.

Here are a few other recent highlights from my outings in the woods following squirrel chatter:

Photograph the Improbable

Now it is time to incorporate some of the insights we discussed in the previous posts into our own photography.

As an example, here is how I did it:

Many of the paintings I was drawn to featured various wildlife in a dramatic setting that told the story of where they live and evoked a mood. I decided to try a new approach in my photography. In this proactive, rather than reactive, mindset I would envision a scene I wanted beforehand and then go after it. I may not have control over all the elements as a painter, but I could use research and knowledge to reduce as many variables as possible and so increase the chances of making a truly remarkable image.

It was September and the peak of the elk rut, so I chose to focus on bull elk with their harems. Creating an image of elk on an dramatic landscape would require some knowledge of animal behavior and environmental factors. Fog always helps to add mood to an image, so water was an important element of the scene. With the basic knowledge that the elk use fairly consistent places to cross the river every morning in order to enter the tree line for cover during the day, and that cold autumn mornings often result in fog covering the river bottom, I was able to significantly increase my chances of getting the shot I envisioned.

Next, I scouted out the scene for several mornings in a row, and even got a few nice images of elk crossing. I still didn’t have the image I envisioned, but the insight I gained from being out in field was invaluable and increased the probability of my vision becoming a reality even more.

A few days later I set out, in the dark and through the woods, to my new location on the river. The plan was to photograph a bull with his harem crossing towards me. Of course, there were still several variables that would need to come together. For example, there would need to be enough light when they crossed, the elk would need to cross at the same time rather than sporadically, and I would need to remain undetected and hidden in the brush on the other side lest the elk become nervous and cross elsewhere. This morning it all came together.

I still wanted one more. All my time photographing these elk in the river was under the mighty shadow of Mount Moran, but none of my images up to this point conveyed that. I wanted a scene that provided the viewer with a perspective of the dramatic landscape in which these creatures live.

This would be a much different and more difficult shot than the previous elk crossings. For starters, I would need to shoot with a wider focal length in order to include the mountain in the scene. I also would need the extremely wary and intelligent elk to cross very close to me so that they would stand out against the rest of the scene. On the tenth morning of sitting in a hunting blind I could hear the sound of hooves behind me. In the moments that followed over one hundred elk crossed in front me.

My aim in sharing this is to inspire you to be intentional with your photography. I want to see more photographers thinking creatively about their work. I would encourage you that it is better get a couple shots that truly stand out over the span of a month, than a thousand that resemble everyone else’s work.

You have your own unique perspective and passions. Let that come to bear on your photography.

How to photograph the sun without permanent eye damage

- Snake River Fog -

One of the first rules people learn in photography, to which they have unwavering fidelity, is always to photograph with the sun at your back. While this a helpful concept in the beginning, the rule, like most "rules" in photography must be broken in order to advance your work beyond the standard family vacation portrait. What sets an experienced photographer apart is not that he/she simply breaks the rules of light, the rule of thirds, etc, but that they have discernment to recognize the situation in which breaking the norms will transform a photograph into a piece of art. Experimenting with frontal light, side light, and back light is an essential step in taking your photography to the next level.

In the case of the image here, I was not simply photographing towards the sun (backlight), but also the sun itself. Properly utilized, this approach can create a dynamic and captivating image. Poorly used, this technique will not only ruin your image, but also your eyesight and thereby future in photography. Here are a few things to consider when including the sun in your photography:

- It can't be the whole sun. I find this really only works in scenarios where the sun is at a low angle (sunrise or sunset) and is partially obscured. My favorite circumstances for this are fog and clouds. In the image above the rising sun was breaking through a fog layer on the bank of the Snake River.

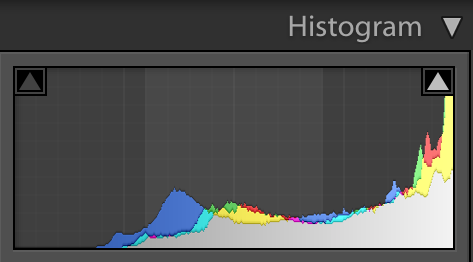

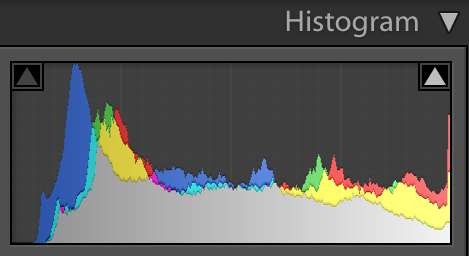

- Underexpose the Image. If you've spent much time dabbling in landscape photography you will have inevitably heard the phrase "always preserve the highlights." This is true...for the most part. Essentially, this means that you always want to expose your image for the brightest part of the scene so that you don't blow out the highlights. However, when you are including the sun itself in the image there will be an inevitable hotspot the blows out the right side of your histogram (as seen below). In this instance I am not concerned with containing all the highlights, but rather I am focused on how large I want that bright spot to be. In this scene I wanted the hotspot to take up roughly a third of the sky. This required me to underexpose the image 2.5 stops.

Phantom of the Wild

“Well…what…are we just going to walk until we step on a wolf?” My friend had a point, this seemed like a real long shot, and there wasn’t a concrete plan. Calculating various factors like time of day, observed patterns, and topography may help increase the probability of wildlife encounters, but in the end a wolf just walks wherever it pleases. I just laughed in response because we both knew this. However, at the same time, we were both compelled to make the grueling bushwhack in the rain. While we fully understood our improbable odds, we also knew that our most memorable and unbelievable moments in the wild only occur when we are actually in the wild.

Only ten minutes had passed and I could no longer resist the urge to stop and set up my camera. The large lens I use travels better in a pack than on my shoulder, but then I am guaranteed to miss the first minute of any photographic opportunity due to the set up time. As I opened the legs of my tripod I heard “There’s a wolf! On the ridge…a white wolf!” What ensued was 45 minutes of the most remarkable individual wolf encounter I’ve ever experienced.

The pursuit of a vision against all odds is at the heart of wildlife photography for me, and no doubt the principle here applies to all facets of our lives. Often the primary obstacle in capturing the most “improbable” moments is not the odds, but myself. It may take time and persistence, but the odds can almost always be overcome. The moment I tell myself “there's no way” it is over before it begins. I encourage you to take some time this week to reflect and identify the “wolf” in your life. What is one thing you are passionate about doing or attaining that seems impossible. If upon mentioning it to most people you receive wide eyes and gaping mouths, then you are likely on the right track. Think big and get out there!

You can only see a wolf if you’re in the wild.