A rare glimpse of a leucistic Great Grey Owl. This anomaly is caused by a lack of pigmentation. This was the male owl of a nesting pair. I had photograhed the females and two chicks for a couple weeks, but had not seen the male, who was typically off hunting, until this day. Just prior to the taking of this image I witnessed the most unique wildlife event of my life, a black bear and two cubs had attempted to climb the nest tree and eat the chicks. The female let out distress calls which prompted the male to come to the nest site, where they both repeatedly dive-bombed the bears until they retreated. After the whole ordeal, the male was tired and rested on this perch for several minutes.

Photographing Grand Teton's Elk in the Fall

The past few days have brought the first taste of fall to the Tetons. The occasional bull elk can now be heard bugling, and sporadic stands of aspens have already transformed into a blazing yellow and orange. I photographed this bull elk with clients the other day during one of my Grand Teton photography tours.

We didn't just luckily stumble across this bull elk standing against the skyline at sunrise. As I have talked about before, the best images are the result of a plan and much thought. We set up on this elk herd in the dark while they were still a long ways off, but I knew, based off of typical elk behavior, that the herd would soon leave the open sagebrush flats and head into woods for cover. They do this every morning around sunrise. So, we positioned ourselves to the west of the elk herd and between their current location and the woods, so that they would pass by us as the rising sun illuminated the clouds in the background. Of course, there were variables out of our control, such as the exact timing the elk would move and the precise path they would take.

Sure enough, the herd began moving towards the timber as the sun broke subtly through the clouds. We had our eye on the bull. As he followed behind cows he began walking this small ridge. One last minute thought played the final role in the making of our image. I needed his whole body to be isolated against the sky, and at first it was only his head and antlers. The mountains were behind the rest of his body. We quickly scrambled down into a ravine in front of us and fell on our knees. Just in time for the bull to pause and turn his head.

Photograph the Improbable

Now it is time to incorporate some of the insights we discussed in the previous posts into our own photography.

As an example, here is how I did it:

Many of the paintings I was drawn to featured various wildlife in a dramatic setting that told the story of where they live and evoked a mood. I decided to try a new approach in my photography. In this proactive, rather than reactive, mindset I would envision a scene I wanted beforehand and then go after it. I may not have control over all the elements as a painter, but I could use research and knowledge to reduce as many variables as possible and so increase the chances of making a truly remarkable image.

It was September and the peak of the elk rut, so I chose to focus on bull elk with their harems. Creating an image of elk on an dramatic landscape would require some knowledge of animal behavior and environmental factors. Fog always helps to add mood to an image, so water was an important element of the scene. With the basic knowledge that the elk use fairly consistent places to cross the river every morning in order to enter the tree line for cover during the day, and that cold autumn mornings often result in fog covering the river bottom, I was able to significantly increase my chances of getting the shot I envisioned.

Next, I scouted out the scene for several mornings in a row, and even got a few nice images of elk crossing. I still didn’t have the image I envisioned, but the insight I gained from being out in field was invaluable and increased the probability of my vision becoming a reality even more.

A few days later I set out, in the dark and through the woods, to my new location on the river. The plan was to photograph a bull with his harem crossing towards me. Of course, there were still several variables that would need to come together. For example, there would need to be enough light when they crossed, the elk would need to cross at the same time rather than sporadically, and I would need to remain undetected and hidden in the brush on the other side lest the elk become nervous and cross elsewhere. This morning it all came together.

I still wanted one more. All my time photographing these elk in the river was under the mighty shadow of Mount Moran, but none of my images up to this point conveyed that. I wanted a scene that provided the viewer with a perspective of the dramatic landscape in which these creatures live.

This would be a much different and more difficult shot than the previous elk crossings. For starters, I would need to shoot with a wider focal length in order to include the mountain in the scene. I also would need the extremely wary and intelligent elk to cross very close to me so that they would stand out against the rest of the scene. On the tenth morning of sitting in a hunting blind I could hear the sound of hooves behind me. In the moments that followed over one hundred elk crossed in front me.

My aim in sharing this is to inspire you to be intentional with your photography. I want to see more photographers thinking creatively about their work. I would encourage you that it is better get a couple shots that truly stand out over the span of a month, than a thousand that resemble everyone else’s work.

You have your own unique perspective and passions. Let that come to bear on your photography.

How to photograph the sun without permanent eye damage

- Snake River Fog -

One of the first rules people learn in photography, to which they have unwavering fidelity, is always to photograph with the sun at your back. While this a helpful concept in the beginning, the rule, like most "rules" in photography must be broken in order to advance your work beyond the standard family vacation portrait. What sets an experienced photographer apart is not that he/she simply breaks the rules of light, the rule of thirds, etc, but that they have discernment to recognize the situation in which breaking the norms will transform a photograph into a piece of art. Experimenting with frontal light, side light, and back light is an essential step in taking your photography to the next level.

In the case of the image here, I was not simply photographing towards the sun (backlight), but also the sun itself. Properly utilized, this approach can create a dynamic and captivating image. Poorly used, this technique will not only ruin your image, but also your eyesight and thereby future in photography. Here are a few things to consider when including the sun in your photography:

- It can't be the whole sun. I find this really only works in scenarios where the sun is at a low angle (sunrise or sunset) and is partially obscured. My favorite circumstances for this are fog and clouds. In the image above the rising sun was breaking through a fog layer on the bank of the Snake River.

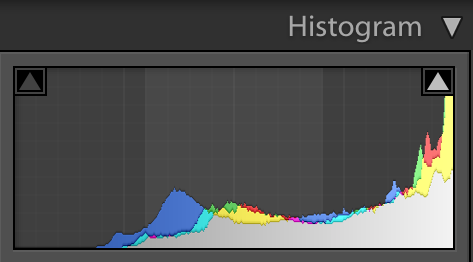

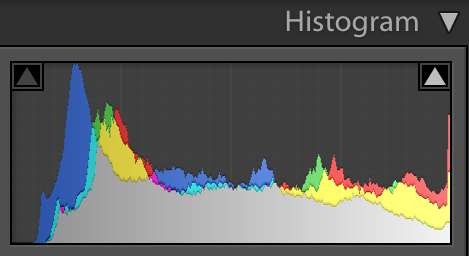

- Underexpose the Image. If you've spent much time dabbling in landscape photography you will have inevitably heard the phrase "always preserve the highlights." This is true...for the most part. Essentially, this means that you always want to expose your image for the brightest part of the scene so that you don't blow out the highlights. However, when you are including the sun itself in the image there will be an inevitable hotspot the blows out the right side of your histogram (as seen below). In this instance I am not concerned with containing all the highlights, but rather I am focused on how large I want that bright spot to be. In this scene I wanted the hotspot to take up roughly a third of the sky. This required me to underexpose the image 2.5 stops.

Phantom of the Wild

“Well…what…are we just going to walk until we step on a wolf?” My friend had a point, this seemed like a real long shot, and there wasn’t a concrete plan. Calculating various factors like time of day, observed patterns, and topography may help increase the probability of wildlife encounters, but in the end a wolf just walks wherever it pleases. I just laughed in response because we both knew this. However, at the same time, we were both compelled to make the grueling bushwhack in the rain. While we fully understood our improbable odds, we also knew that our most memorable and unbelievable moments in the wild only occur when we are actually in the wild.

Only ten minutes had passed and I could no longer resist the urge to stop and set up my camera. The large lens I use travels better in a pack than on my shoulder, but then I am guaranteed to miss the first minute of any photographic opportunity due to the set up time. As I opened the legs of my tripod I heard “There’s a wolf! On the ridge…a white wolf!” What ensued was 45 minutes of the most remarkable individual wolf encounter I’ve ever experienced.

The pursuit of a vision against all odds is at the heart of wildlife photography for me, and no doubt the principle here applies to all facets of our lives. Often the primary obstacle in capturing the most “improbable” moments is not the odds, but myself. It may take time and persistence, but the odds can almost always be overcome. The moment I tell myself “there's no way” it is over before it begins. I encourage you to take some time this week to reflect and identify the “wolf” in your life. What is one thing you are passionate about doing or attaining that seems impossible. If upon mentioning it to most people you receive wide eyes and gaping mouths, then you are likely on the right track. Think big and get out there!

You can only see a wolf if you’re in the wild.

"Grizzly Shadows" - Turning Harsh Light Into a Beautiful Photograph

After the initial excitement of finding this grizzly in the Tetons I was confronted with the difficulty of creating an image with the contrasting light. All of the scenes seemed to contain either dark shadows or harsh light, neither of which are pleasing to the eye on their own. There was one possibility…but it would take a bit of luck. I would need a scene where the light illuminated only the bears face, while leaving the majority of the scene in shadows. If this came together, then I could underexpose the image by 3 full stops in order to reduce the chaos in the backdrop by turning it black. I would also need to position myself as low as possible to create the shallowest depth of field possible, which blurs the background. These two elements combined (the darkness and blur) allowed me to a create an image that was pleasing to the eye in conditions that otherwise were not.

"Fog Crossing" - How Knowledge of Wildlife Behavior Informs Photography

I had visualized this shot long before it came together. I knew that the elk crossed the river at dawn every morning to head into the timber for cover, so I had that going for me. However, where exactly they cross and whether there would be enough light for a photograph was an unknown, and then add that elk are extremely intelligent and wary, so they spook easily. As I set out in the dark before sunrise I could the bull bugling nearby. I quietly hiked to my spot and waited, meantime the prehistoric scream was getting louder and louder. Just as there was enough light on the river the bull appeared on the bank and began swimming across the river.